Archive

Book presentation at the USC Python Users Group

More on Lindenmayer Systems

We briefly explored Lindenmayer systems (or L-systems) in an old post: Toying with Basic Fractals. We quickly reviewed this method for creation of an approximation to fractals, and displayed an example (the Koch snowflake) based on tikz libraries.

I would like to show a few more examples of beautiful curves generated with this technique, together with their generating axiom, rules and parameters. Feel free to click on each of the images below to download a larger version.

Note that any coding language with plotting capabilities should be able to tackle this project. I used once again tikz for , but this time with the tikzlibrary lindenmayersystems.

Would you like to experiment a little with axioms, rules and parameters, and obtain some new pleasant curves with this method? If the mathematical properties of the fractal that they approximate are interesting enough, I bet you could attach your name to them. Like the astronomer that finds through her telescope a new object in the sky, or the zoologist that discover a new species of spider in the forest.

Sympy should suffice

I have just received a copy of Instant SymPy Starter, by Ronan Lamy—a no-nonsense guide to the main properties of SymPy, the Python library for symbolic mathematics. This short monograph packs everything you should need, with neat examples included, in about 50 pages. Well-worth its money.

To celebrate, I would like to pose a few coding challenges on the use of this library, based on a fun geometric puzzle from cut-the-knot: Rhombus in Circles

Segments

and

are equal. Lines

and

intersect at

Form four circumcircles:

Prove that the circumcenters

form a rhombus, with

Note that if this construction works, it must do so independently of translations, rotations and dilations. We may then assume that is the origin, that the segments have length one,

and that for some parameters

it is

We let SymPy take care of the computation of circumcenters:

import sympy

from sympy import *

# Point definitions

M=Point(0,0)

A=Point(2,0)

B=Point(1,0)

a,theta=symbols('a,theta',real=True,positive=True)

C=Point((a+1)*cos(theta),(a+1)*sin(theta))

D=Point(a*cos(theta),a*sin(theta))

#Circumcenters

E=Triangle(A,C,M).circumcenter

F=Triangle(A,D,M).circumcenter

G=Triangle(B,D,M).circumcenter

H=Triangle(B,C,M).circumcenter

Finding that the alternate angles are equal in the quadrilateral is pretty straightforward:

In [11]: P=Polygon(E,F,G,H) In [12]: P.angles[E]==P.angles[G] Out[12]: True In [13]: P.angles[F]==P.angles[H] Out[13]: True

To prove it a rhombus, the two sides that coincide on each angle must be equal. This presents us with the first challenge: Note for example that if we naively ask SymPy whether the triangle is equilateral, we get a False statement:

In [14]: Triangle(E,F,G).is_equilateral() Out[14]: False In [15]: F.distance(E) Out[15]: Abs((a/2 - cos(theta))/sin(theta) - (a - 2*cos(theta) + 1)/(2*sin(theta))) In [16]: F.distance(G) Out[16]: sqrt(((a/2 - cos(theta))/sin(theta) - (a - cos(theta))/(2*sin(theta)))**2 + 1/4)

Part of the reason is that we have not indicated anywhere that the parameter theta is to be strictly bounded above by (we did indicate that it must be strictly positive). The other reason is that SymPy does not handle identities well, unless the expressions to be evaluated are perfectly simplified. For example, if we trust the routines of simplification of trigonometric expressions alone, we will not be able to resolve this problem with this technique:

In [17]: trigsimp(F.distance(E)-F.distance(G),deep=True)==0 Out[17]: False

Finding that with SymPy is not that easy either. This is the second challenge.

How would the reader resolve this situation?

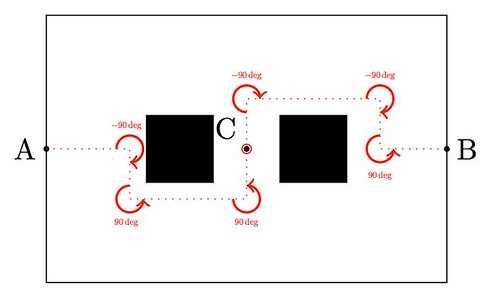

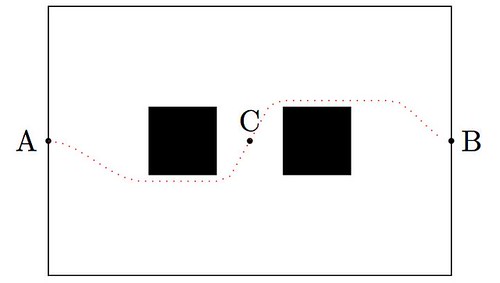

Edge detection: The Convolution Approach

Today I would like to show a very basic technique of detection based on simple convolution of an image with small kernels (masks). The purpose of these kernels is to enhance certain properties of the image at each pixel. What properties? Those that define what means to be an edge, in a differential calculus way—exactly as it was defined in the description of the Canny edge detector. The big idea is to assign to each pixel a numerical value that expresses its strength as an edge: positive if we suspect that such structure is present at that location, negative if not, and zero if the image is locally flat around that point. Masks can be designed so that they mimic the effect of differential operators, but these can be terribly complicated and give rise to large matrices.

The first approaches were performed with simple kernels. For example, Faler came up with the following four simple masks that emulate differentiation:

Note that, adding all the values of each matrix, one obtains zero. This is consistent with the third property required for our kernels: in the event of a locally flat area around a given pixel, convolution with any of these will offer a value of zero.

Math Genealogy Project

I traced my mathematical lineage back into the XIV century at The Mathematics Genealogy Project. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that a big branch in the tree of my scientific ancestors is composed not by mathematicians, but by big names in the fields of Physics, Chemistry, Physiology and even Anatomy.

I traced my mathematical lineage back into the XIV century at The Mathematics Genealogy Project. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that a big branch in the tree of my scientific ancestors is composed not by mathematicians, but by big names in the fields of Physics, Chemistry, Physiology and even Anatomy.

There is some “blue blood” in my family: Garrett Birkhoff, William Burnside (both algebrists). Archibald Hill, who shared the 1922 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his elucidation of the production of mechanical work in muscles. He is regarded, along with Hermann Helmholtz, as one of the founders of Biophysics.

Thomas Huxley (a.k.a. “Darwin’s Bulldog”, biologist and paleontologist) participated in that famous debate in 1860 with the Lord Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce. This was a key moment in the wider acceptance of Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution.

There are some hard-core scientists in the XVIII century, like Joseph Barth and Georg Beer (the latter is notable for inventing the flap operation for cataracts, known today as Beer’s operation).

My namesake Franciscus Sylvius, another professor in Medicine, discovered the cleft in the brain now known as Sylvius’ fissure (circa 1637). One of his advisors, Jan Baptist van Helmont, is the founder of Pneumatic Chemistry and disciple of Paracelsus, the father of Toxicology (for some reason, the Mathematics Genealogy Project does not list any of these two in my lineage—I wonder why).

There are other big names among the branches of my scientific genealogy tree, but I will postpone this discovery towards the end of the post, for a nice punch-line.

Posters with your genealogy are available for purchase from the pages of the Mathematics Genealogy Project, but they are not very flexible neither in terms of layout nor design in general. A great option is, of course, doing it yourself. With the aid of python, GraphViz and a the sage library networkx, this becomes a straightforward task. Let me show you a naïve way to accomplish it:

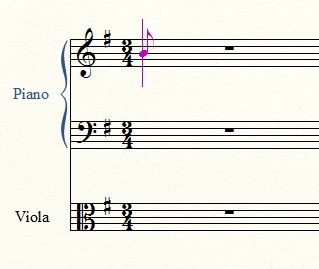

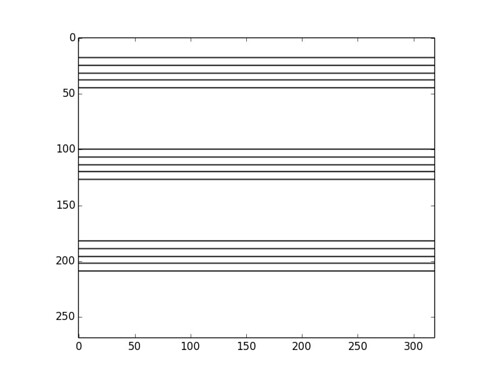

Wavelets in sage

There are no native wavelet packages in sage. But there is a great module in python that contains, among other things, forward and inverse discrete wavelet transforms (for one and two dimensions). It comes bundled with seventy-six wavelet filters, and allows support to build your own! The name is PyWavelets, written by Tariq Rashid, and can be retrieved from pypi.python.org/pypi/PyWavelets. In order to install it in sage, take the following steps: