Archive

Searching (again!?) for the SS Central America

On Tuesday, September 8th 1857, the steamboat SS Central America left Havana at 9 AM for New York, carrying about 600 passengers and crew members. Inside of this vessel, there was stowed a very precious cargo: a set of manuscripts by John James Audubon, and three tons of gold bars and coins. The manuscripts documented an expedition through the yet uncharted southwestern United States and California, and contained 200 sketches and paintings of its wildlife. The gold, fruit of many years of prospecting and mining during the California Gold Rush, was meant to start anew the lives of many of the passengers aboard.

On the 9th, the vessel ran into a storm which developed into a hurricane. The steamboat endured four hard days at sea, and by Saturday morning the ship was doomed. The captain arranged to have women and children taken off to the brig Marine, which offered them assistance at about noon. In spite of the efforts of the remaining crew and passengers to save the ship, the inevitable happened at about 8 PM that same day. The wreck claimed the lives of 425 men, and carried the valuable cargo to the bottom of the sea.

It was not until late 1980s that technology allowed recovery of shipwrecks at deep sea. But no technology would be of any help without an accurate location of the site. In the following paragraphs we would like to illustrate the power of the scipy stack by performing a simple simulation, that ultimately creates a dataset of possible locations for the wreck of the SS Central America, and mines the data to attempt to pinpoint the most probable target.

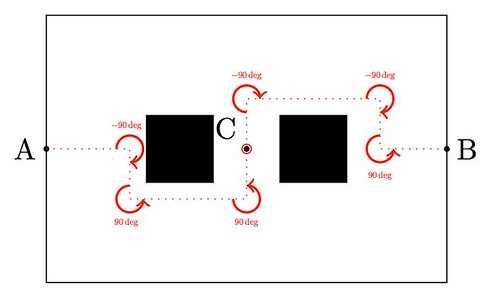

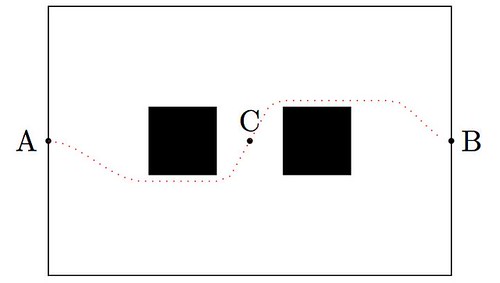

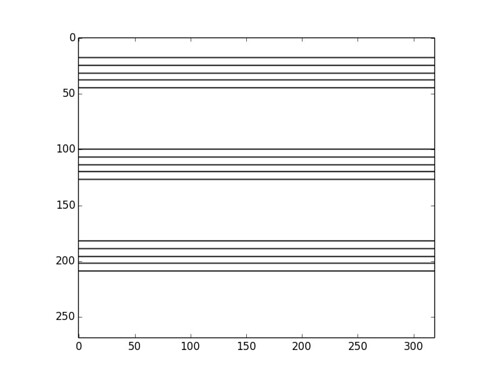

We simulate several possible paths of the steamboat (say 10,000 randomly generated possibilities), between 7:00 AM on Saturday, and 13 hours later, at 8:00 pm on Sunday. At 7:00 AM on that Saturday the ship’s captain, William Herndon, took a celestial fix and verbally relayed the position to the schooner El Dorado. The fix was 31º25′ North, 77º10′ West. Because the ship was not operative at that point—no engine, no sails—, for the next thirteen hours its course was solely subjected to the effect of ocean current and winds. With enough information, it is possible to model the drift and leeway on different possible paths.

Book presentation at the USC Python Users Group

Areas of Mathematics

For one of my upcoming talks I am trying to include an exhaustive mindmap showing the different areas of Mathematics, and somehow, how they relate to each other. Most of the information I am using has been processed from years of exposure in the field, and a bit of help from Wikipedia.

But I am not entirely happy with what I see: my lack of training in the area of Combinatorics results in a rather dry treatment of that part of the mindmap, for example. I am afraid that the same could be told about other parts of the diagram. Any help from the reader to clarify and polish this information will be very much appreciated.

And as a bonus, I included a script to generate the diagram with the aid of the tikz libraries.

\tikzstyle{level 2 concept}+=[sibling angle=40]

\begin{tikzpicture}[scale=0.49, transform shape]

\path[mindmap,concept color=black,text=white]

node[concept] {Pure Mathematics} [clockwise from=45]

child[concept color=DeepSkyBlue4]{

node[concept] {Analysis} [clockwise from=180]

child {

node[concept] {Multivariate \& Vector Calculus}

[clockwise from=120]

child {node[concept] {ODEs}}}

child { node[concept] {Functional Analysis}}

child { node[concept] {Measure Theory}}

child { node[concept] {Calculus of Variations}}

child { node[concept] {Harmonic Analysis}}

child { node[concept] {Complex Analysis}}

child { node[concept] {Stochastic Analysis}}

child { node[concept] {Geometric Analysis}

[clockwise from=-40]

child {node[concept] {PDEs}}}}

child[concept color=black!50!green, grow=-40]{

node[concept] {Combinatorics} [clockwise from=10]

child {node[concept] {Enumerative}}

child {node[concept] {Extremal}}

child {node[concept] {Graph Theory}}}

child[concept color=black!25!red, grow=-90]{

node[concept] {Geometry} [clockwise from=-30]

child {node[concept] {Convex Geometry}}

child {node[concept] {Differential Geometry}}

child {node[concept] {Manifolds}}

child {node[concept,color=black!50!green!50!red,text=white] {Discrete Geometry}}

child {

node[concept] {Topology} [clockwise from=-150]

child {node [concept,color=black!25!red!50!brown,text=white]

{Algebraic Topology}}}}

child[concept color=brown,grow=140]{

node[concept] {Algebra} [counterclockwise from=70]

child {node[concept] {Elementary}}

child {node[concept] {Number Theory}}

child {node[concept] {Abstract} [clockwise from=180]

child {node[concept,color=red!25!brown,text=white] {Algebraic Geometry}}}

child {node[concept] {Linear}}}

node[extra concept,concept color=black] at (200:5) {Applied Mathematics}

child[grow=145,concept color=black!50!yellow] {

node[concept] {Probability} [clockwise from=180]

child {node[concept] {Stochastic Processes}}}

child[grow=175,concept color=black!50!yellow] {node[concept] {Statistics}}

child[grow=205,concept color=black!50!yellow] {node[concept] {Numerical Analysis}}

child[grow=235,concept color=black!50!yellow] {node[concept] {Symbolic Computation}};

\end{tikzpicture}

Have a child, plant a tree, write a book

Or more importantly: rear your children to become nice people, water those trees, and make sure that your books make a good impact.

I recently enjoyed the rare pleasure of having a child (my first!) and publishing a book almost at the same time. Since this post belongs in my professional blog, I will exclusively comment on the latter: Learning SciPy for Numerical and Scientific Computing, published by Packt in a series of technical books focusing on Open Source software.

Keep in mind that the book is for a very specialized audience: not only do you need a basic knowledge of Python, but also a somewhat advanced command of mathematics/physics, and an interest in engineering or scientific applications. This is an excerpt of the detailed description of the monograph, as it reads in the publisher’s page:

It is essential to incorporate workflow data and code from various sources in order to create fast and effective algorithms to solve complex problems in science and engineering. Data is coming at us faster, dirtier, and at an ever increasing rate. There is no need to employ difficult-to-maintain code, or expensive mathematical engines to solve your numerical computations anymore. SciPy guarantees fast, accurate, and easy-to-code solutions to your numerical and scientific computing applications.

Learning SciPy for Numerical and Scientific Computing unveils secrets to some of the most critical mathematical and scientific computing problems and will play an instrumental role in supporting your research. The book will teach you how to quickly and efficiently use different modules and routines from the SciPy library to cover the vast scope of numerical mathematics with its simplistic practical approach that is easy to follow.

The book starts with a brief description of the SciPy libraries, showing practical demonstrations for acquiring and installing them on your system. This is followed by the second chapter which is a fun and fast-paced primer to array creation, manipulation, and problem-solving based on these techniques.

The rest of the chapters describe the use of all different modules and routines from the SciPy libraries, through the scope of different branches of numerical mathematics. Each big field is represented: numerical analysis, linear algebra, statistics, signal processing, and computational geometry. And for each of these fields all possibilities are illustrated with clear syntax, and plenty of examples. The book then presents combinations of all these techniques to the solution of research problems in real-life scenarios for different sciences or engineering — from image compression, biological classification of species, control theory, design of wings, to structural analysis of oxides.

The book is also being sold online in Amazon, where it has been received with pretty good reviews. I have found other random reviews elsewhere, with similar welcoming comments:

- Artificial Intelligence in Motion by Marcel Caraciolo

- The Endeavour, by John D. Cook

Which one is the fake?

|

|

|

“Crab on its back” | “Willows at sunset” | “Still life: Potatoes in a yellow dish” |

So you want to be an Applied Mathematician

The way of the Applied Mathematician is one full of challenging and interesting problems. We thrive by association with the Pure Mathematician, and at the same time with the no-nonsense, hands-in, hard-core Engineer. But not everything is happy in Applied Mathematician land: every now and then, we receive the disregard of other professionals that mistake either our background, or our efficiency at attacking real-life problems.

I heard from a colleague (an Algebrist) complains that Applied Mathematicians did nothing but code solutions of partial differential equations in Fortran—his skewed view came up after a naïve observation of a few graduate students working on a project. The truth could not be further from this claim: we do indeed occasionally solve PDEs in Fortran—I give you that—and we are not ashamed to admit it. But before that job has to be addressed, we have gone through a great deal of thinking on how to better code this simple problem. And you would not believe the huge amount of deep Mathematics that are involved in this journey: everything from high-level Linear Algebra, Calculus of Variations, Harmonic Analysis, Differential Geometry, Microlocal Analysis, Functional Analysis, Dynamical Systems, the Theory of Distributions, etc. Not only are we familiar with the basic background on all those fields, but also we are supposed to be able to perform serious research on any of them at a given time.

My soon-to-be-converted Algebrist friend challenged me—not without a hint of smugness in his voice—to illustrate what was my last project at that time. This was one revolving around the idea of frames (think of it as redundant bases if you please), and needed proving a couple of inequalities involving sequences of functions in —spaces, which we attacked using a beautiful technique: Bellman functions. About ninety minutes later he conceded defeat in front of the board where the math was displayed. He promptly admitted that this was no Fortran code, and showed a newfound respect and reverence for the trade.

It doesn’t hurt either that the kind of problems that we attack are more likely to attract funding. And collaboration. And to be noticed in the press.

Alright, so some of you are sold already. What is the next step? I am assuming that at his point you own your Calculus, Analysis, Probability and Statistics, Linear Programming, Topology, Geometry, Physics and you are able to solve most known ODEs. From here, as with any other field, my recommendation is to slowly build a Batman belt: acquire and devour a sequence of books and scientific articles, until you are very familiar with their contents. When facing a new problem, you should be able to recall from your Batman belt what technique could work best, in which book(s) you could get some references, and how it has been used in the past for related problems.

Following these lines, I have included below an interesting collection with the absolutely essential books that, in my opinion, every Applied Mathematician should start studying:

Unusual dice

I heard of this problem from Justin James in his TechRepublic post My First IronRuby Application. He tried this fun problem as a toy example to brush up his skills in ruby:

I heard of this problem from Justin James in his TechRepublic post My First IronRuby Application. He tried this fun problem as a toy example to brush up his skills in ruby:

Roll simultaneously a hundred 100-sided dice, and add the resulting values. The set of possible outcomes is, of course, Note that there is only one way to obtain the outcome 100—all dice showing a 1. There is also only one way to obtain the outcome 10000—all dice showing 100. For the outcome 101, there are exactly 100 different ways to obtain it: all dice except one show a 1, and one die shows a 2. The follow-up question is:

Write a (fast) script that computes the different ways in which we can obtain each of the possible outcomes.

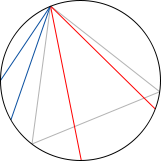

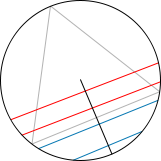

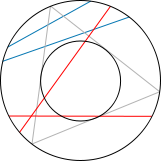

Bertrand Paradox

Classically, we define the probability of an event as the ratio of the favorable cases, over the number of all possible cases. Of course, these possible cases need to be all equally likely. This works great for discrete settings, like dice rolls, card games, etc. But when facing non-discrete cases, this definition needs to be revised, as the following example shows:

Consider an equilateral triangle inscribed in a circle. Suppose a chord of the circle is chosen at random. What is the probability that the chord is longer than a side of the triangle?

First example Second example Third example